No, no it didn’t. ⋞Something Happened Here: Roswell prepares for Pentagon’s UFO report⋟ On the eve of the release of the Pentagon’s highly anticipated report on unidentified aerial phenomena, life here in one of the world’s UFO hotspots was exceedingly normal. Downtown’s alien souvenir shops and the International UFO Museum welcomed a steady stream of…

Category: History

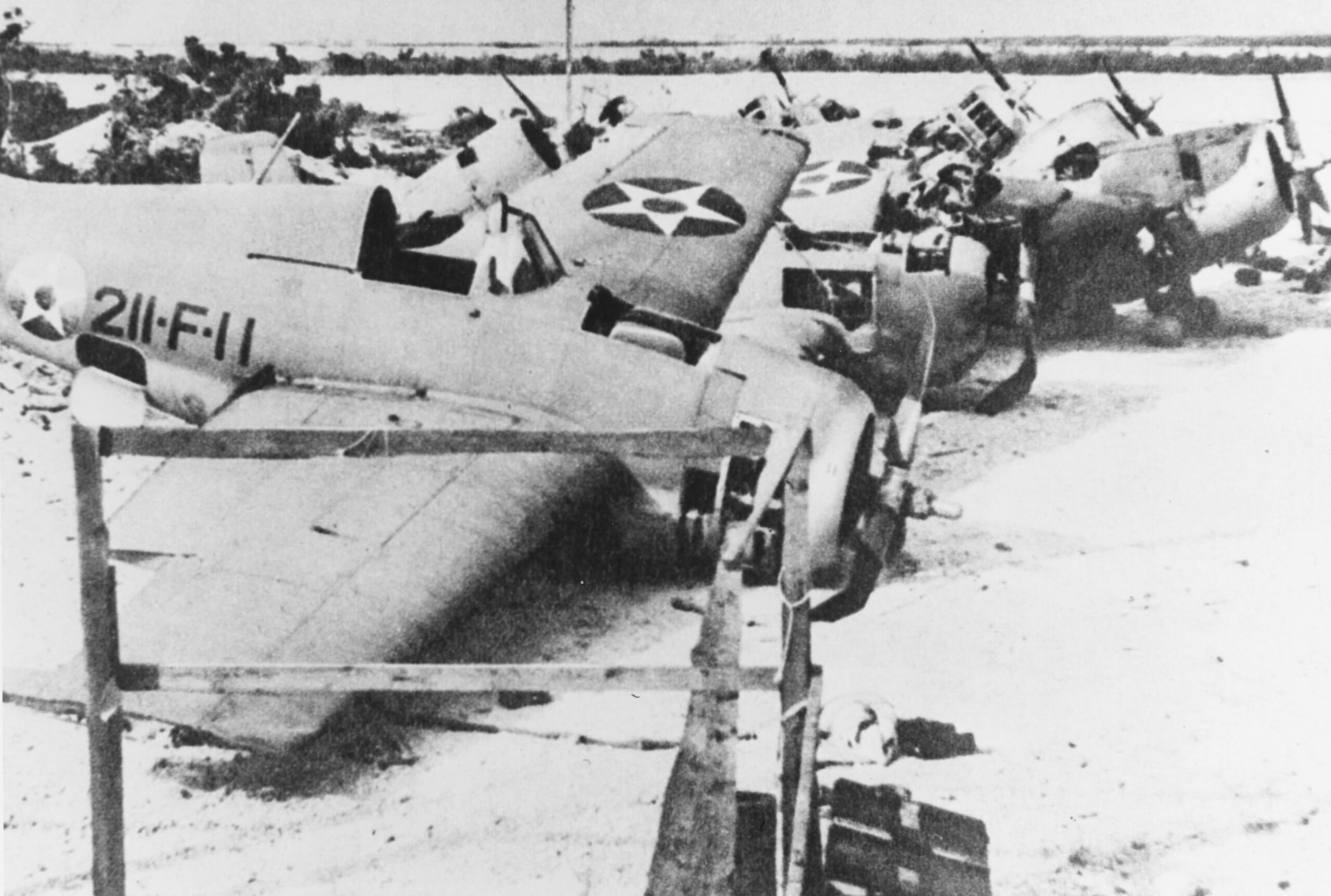

The Wake Island Story, Part I

Memory Of WWII Still Vivid for Vets (Part I of the Wake Island Story) “Considering the power accumulated for the invastion of Wake Island and the meager forces of the defenders, it was one of the most humiliating defeats the Japanese Navy ever suffered.” —Masatake Okumiya, commander, Japanese Imperial Navy By Steve PollockThe Duncan (OK)…

The Wake Island Story Part II

Wives Cope With Husband’s Memories (Part 2 of the Wake Island Story) By Steve PollockThe Duncan (OK) Banner)Sunday, August 13, 1989 MARLOW — It all came back to them this weekend — fists lashing out during nightmares, the traumatic memories, the attempts to catch up on lost time. The wives of 10 Wake Island survivors…

Sticky Seats to Sherman

I used the road and some parallel ones once in 1975 to get from our house in Oklahoma to my aunt’s house in Sherman, TX. My cousins had been staying with us. Our grandparents, in their Ford Torino, took us to Sherman. We spent the night and came back to Duncan. It was hot. Damn…