I used the road and some parallel ones once in 1975 to get from our house in Oklahoma to my aunt’s house in Sherman, TX. My cousins had been staying with us. Our grandparents, in their Ford Torino, took us to Sherman. We spent the night and came back to Duncan. It was hot. Damn…

Time to Hit the Road

It’s time to cut my losses and admit it’s time to hit the road on what I believe will be my last career .. on the road, trucking. (How’s that for a sentence?) Working 911 was an interesting year. Fascinating, appalling. Ultimately, the callers didn’t drive me away. The calls didn’t drive me away. The center, which is actually one of the better ones in the country, drove me away. Three problems: Training is a debacle; communications is non-existent; and I hated police dispatch. So, I’ve called time. I gave it a solid year. But by the end of April, I could tell the writing was on the wall.

Nothing to Say

I have nothing to say. On paper. Probably in person. Mute all my life except brief bursts of productivity. Newspaper/school PR work 1088=1994. Northpoint Communications internal PR 1998-2000. That’s work. But what can I write personally? There’s a story about eternal life I’ve worked on for years. Another book about plane crashes— midairs this time….

Nope

No, no it didn’t. ⋞Something Happened Here: Roswell prepares for Pentagon’s UFO report⋟ On the eve of the release of the Pentagon’s highly anticipated report on unidentified aerial phenomena, life here in one of the world’s UFO hotspots was exceedingly normal. Downtown’s alien souvenir shops and the International UFO Museum welcomed a steady stream of…

The Road

I dream of a different future which might just be possible only if I win a lottery. Or a semi-truck runs over us and a TV lawyer collects a big ol’ settlement. A house. Built from scratch. In my home state. A meditation/de-stressing center where anyone can go to have some simple peace and quiet…

Revenge is Sweet

[Just a startling dream i had, profanity included. None of this happened or is real. Just to be clear.] We went to another school as a group, supposedly for professional development. We observed some teachers in their classrooms. I brought a label maker and showed some way to make fancy, gold-leaf labels using some expensive…

#EmptyThePews

FRICKIN’ HOLY MARY MOTHER OF GOD! JESUS MARY AND JOSEPH! POPE PAUL VI AND ALL THE SAINTS! AND DEAR GOD WHY ARE ALL THESE WOMEN IN EXPENSIVE ULTRASUEDE DRESSES RUNNING UP AND DOWN THE AISLES SCREAMING THEIR FOOL HEADS OFF???!!!!!

Your Travel Guide to Baghdad-By-The-Bay (2002)

[A longish screed about things to see and do as a tourist in San Francisco in 2002, written for a friend. Many of the links, being 20 years old, may not work.—Ed.] ‘I sat in the Delhi airport and watched the big electric clock in the departure hall that tells passengers when to board. I…

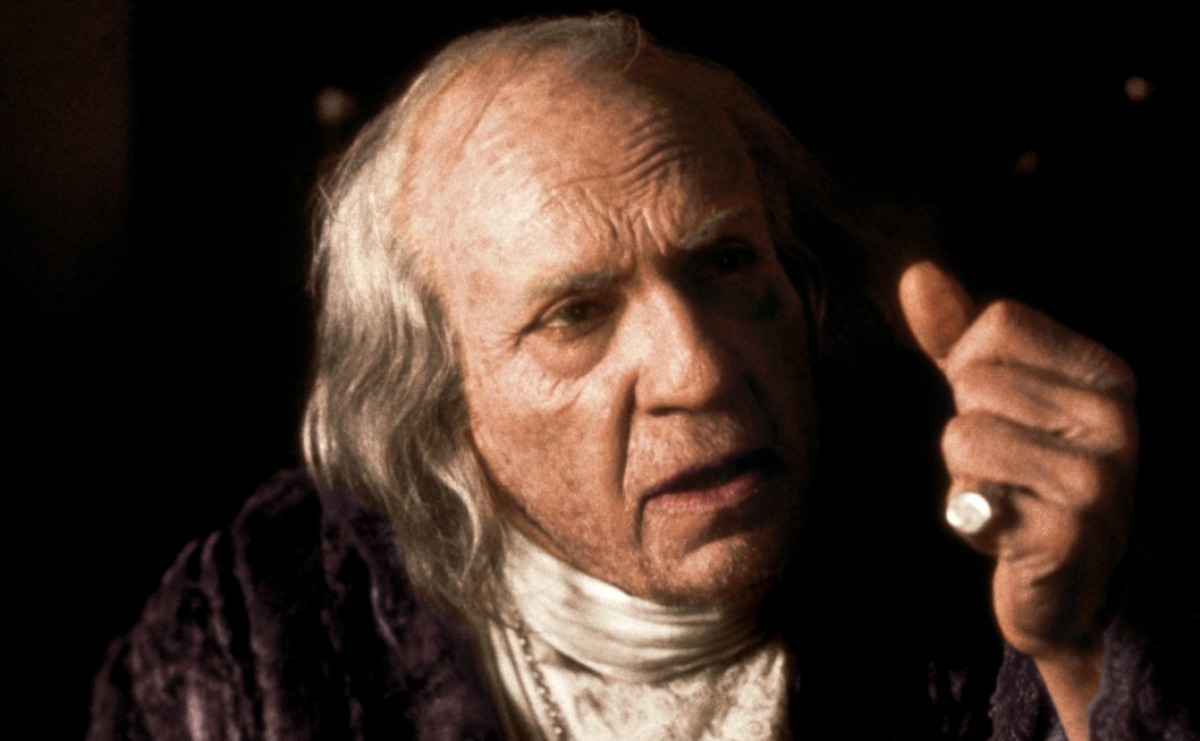

A Eulogy for Brooksie Belle Ketchum Booth, My Grandmother

[I wrote the following passages in two separate sections over two separate days.] Part I – 2:00 a.m. San Francisco Time, Wednesday, Nov. 14, 2001The call I was dreading came just ten minutes ago – an unhappy, middle-of-the-night call — word from my exhausted and grief-stricken mother that her mother’s long battle was over and…

A Memory of My Grandfather

I am inordinately proud of all my grandparents, proud of their heritage and what they did and gave to us. All of them worked extremely hard under difficult circumstances to bring, in their own way, the basics of life, love, and happiness to their families. We enjoy the blessed lives we have in no small…

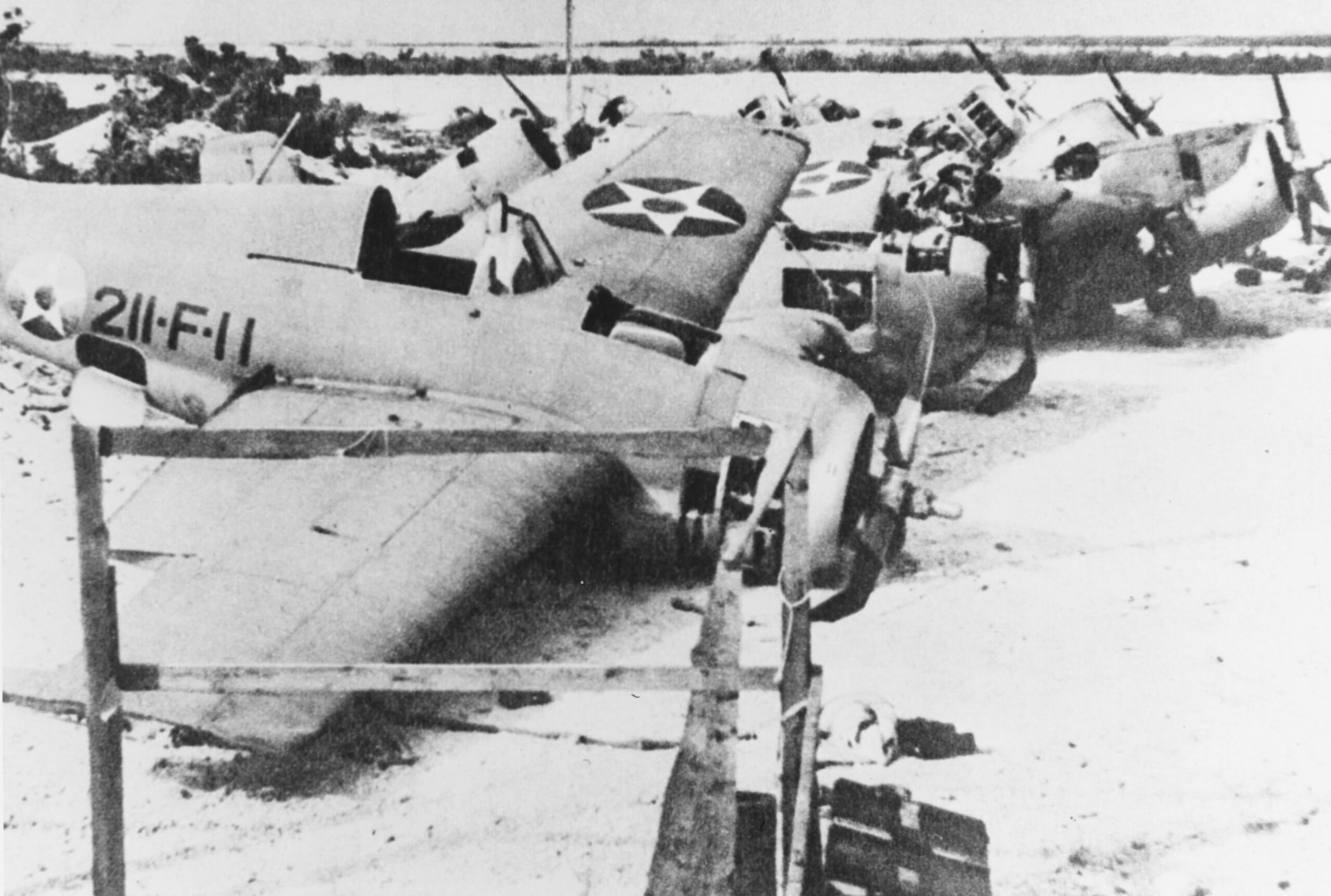

The Wake Island Story, Part I

Memory Of WWII Still Vivid for Vets (Part I of the Wake Island Story) “Considering the power accumulated for the invastion of Wake Island and the meager forces of the defenders, it was one of the most humiliating defeats the Japanese Navy ever suffered.” —Masatake Okumiya, commander, Japanese Imperial Navy By Steve PollockThe Duncan (OK)…